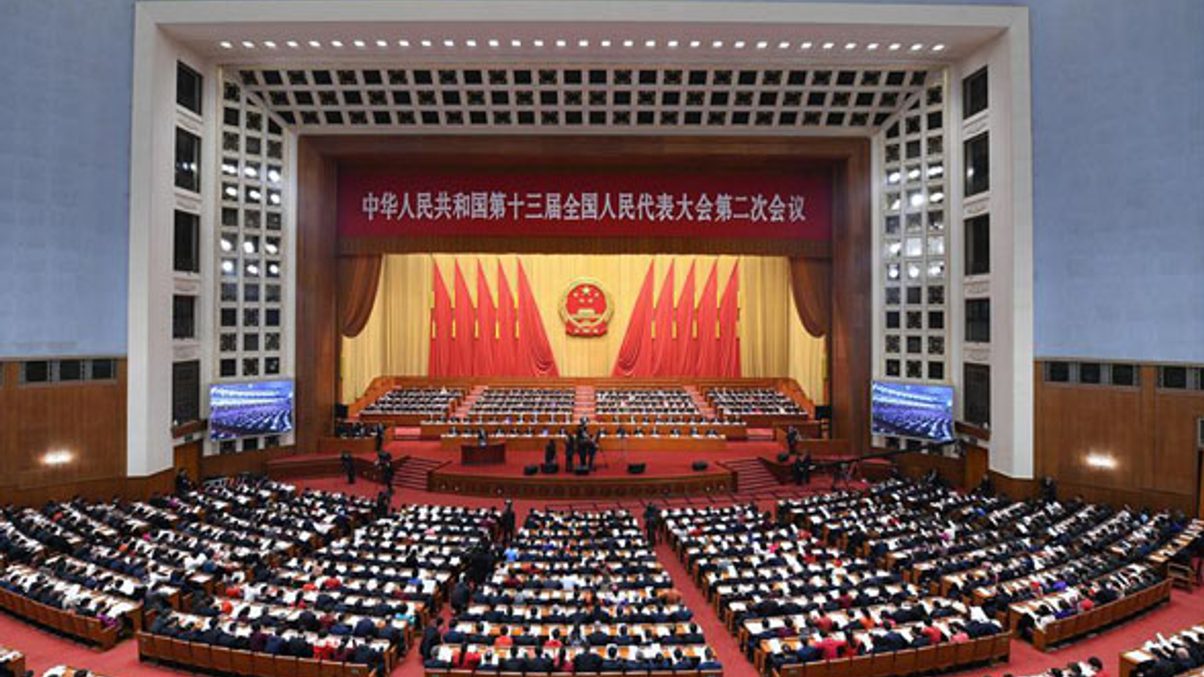

Market Views: What do the “Two Sessions” say about China?

What are Beijing's economic priorities this year, and how much will China's economy expand in 2020? Seven experts shared their opinions.

China's tightly-managed economy rarely misses its GDP growth target. That all changed with Covid-19. In the first quarter of this year, China's economy contracted 6.8% year-on-year - its worst GDP performance in over 40 years.

Sign in to read on!

Registered users get 2 free articles in 30 days.

Subscribers have full unlimited access to AsianInvestor

Not signed up? New users get 2 free articles per month, plus a 7-day unlimited free trial.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.