Market Views: How could the deglobalisation of supply chains impact Asian investors?

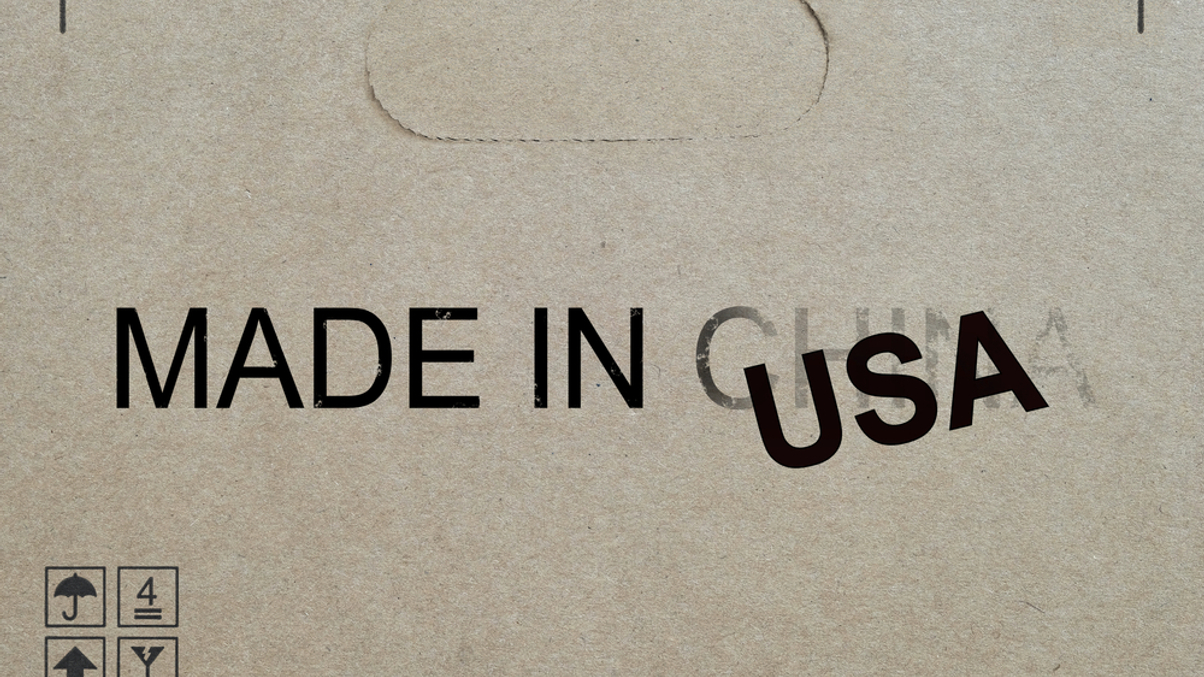

Deglobalisation is not a new concept to investors, but what risks and opportunities would the decoupling and onshoring of the world’s supply chains present Asia’s investment landscape?

Amid reports of deglobalisation having been accelerated by a post-Covid economy and geopolitical tensions, analysts have viewed the shift as an evolution of globalisation or "reglobalisation" as they eye investment opportunities in Asia.

Sign in to read on!

Registered users get 2 free articles in 30 days.

Subscribers have full unlimited access to AsianInvestor

Not signed up? New users get 2 free articles per month, plus a 7-day unlimited free trial.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.