ESG in question as investors fail the Russia test: experts

Institutional funds haven't done enough to ensure they are not supporting hostile and repressive regimes with their investors' capital, according to ESG industry leaders.

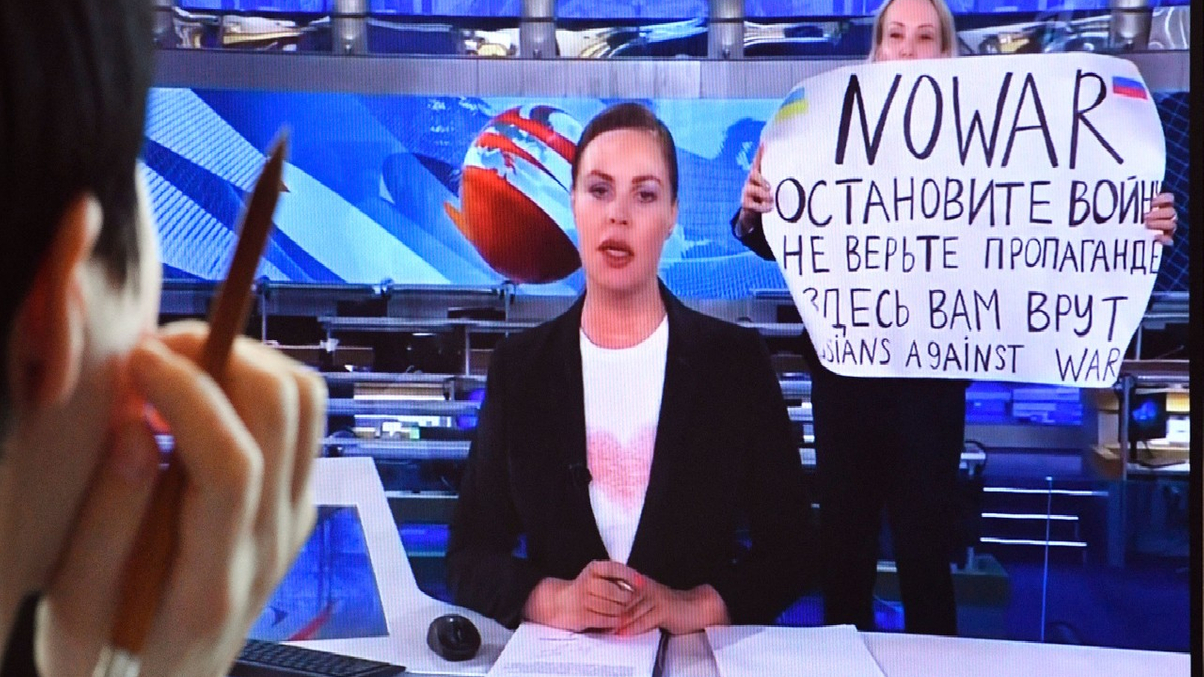

In the midst of the ongoing invasion of Ukraine by Russia, questions are being asked of the investment and business community. Have they enabled Russia by not holding it to the standards of governance and human rights they purport to uphold by their ESG statements?

Sign in to read on!

Registered users get 2 free articles in 30 days.

Subscribers have full unlimited access to AsianInvestor

Not signed up? New users get 2 free articles per month, plus a 7-day unlimited free trial.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.