Private banks weigh in on robo fund selectors

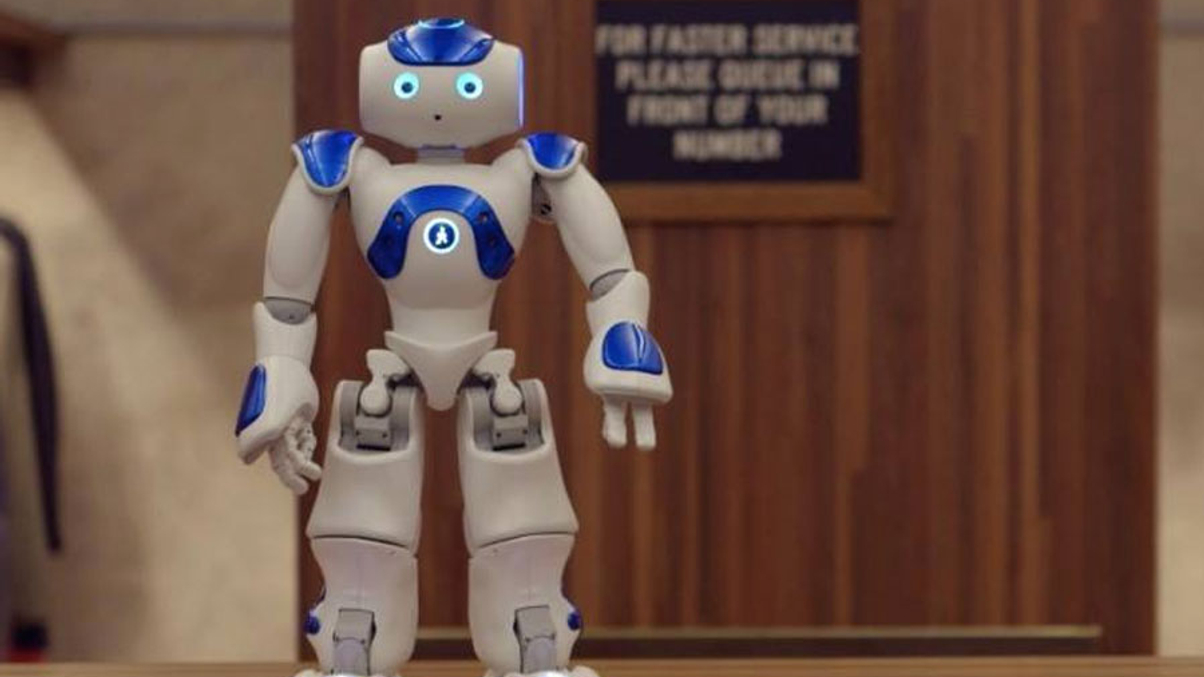

Automated investing is spreading into wealth managers' fund distribution. But it will probably complement service providers not replace them, we report in the first of a two-part article.

Asia wealth managers beware: the robot revolution is entering its next phase.

Sign in to read on!

Registered users get 2 free articles in 30 days.

Subscribers have full unlimited access to AsianInvestor

Not signed up? New users get 2 free articles per month, plus a 7-day unlimited free trial.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.