AI 15: World faces slowing growth, says GMO's Grantham

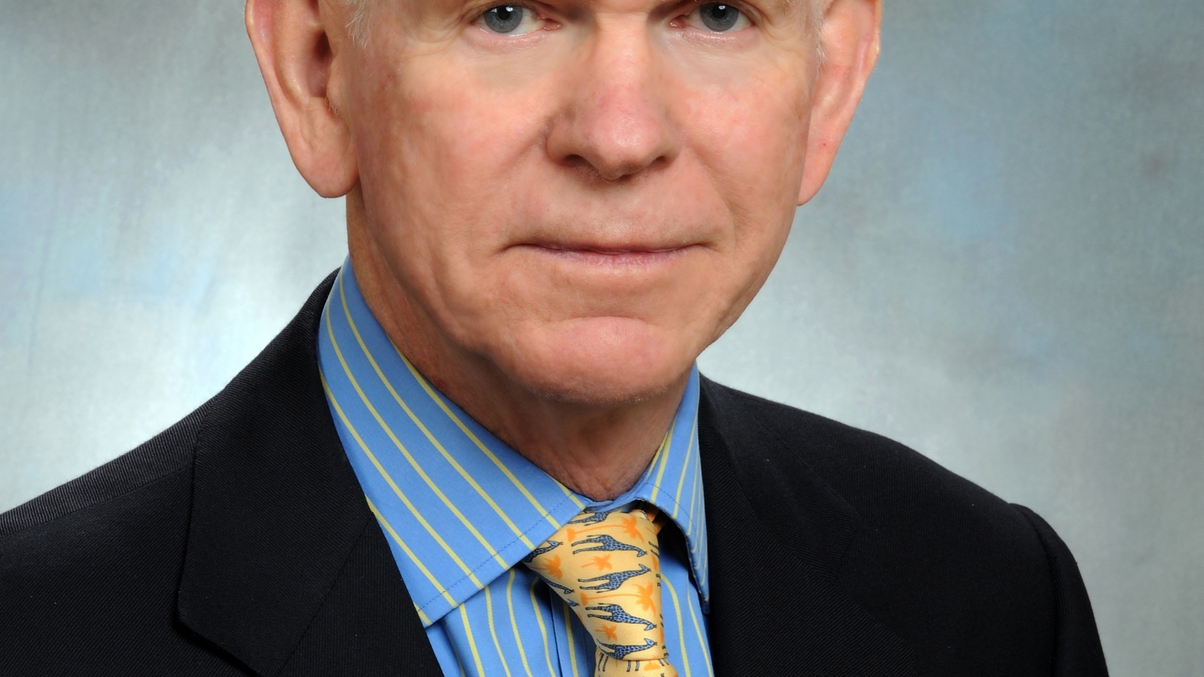

Jeremy Grantham, chief investment strategist at asset manager GMO, predicts oil prices will return to $100 a barrel, but GDP growth will disappoint. This is the first of a two-part interview with the GMO co-founder.

As part of our 15th anniversary celebrations, AsianInvestor asked Jeremy Grantham, co-founder of GMO, the Boston-based partnership, to give us his predictions about the global trends that will shape the next 20 years. The second part of the interview will be published tomorrow.

Sign in to read on!

Registered users get 2 free articles in 30 days.

Subscribers have full unlimited access to AsianInvestor

Not signed up? New users get 2 free articles per month, plus a 7-day unlimited free trial.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.