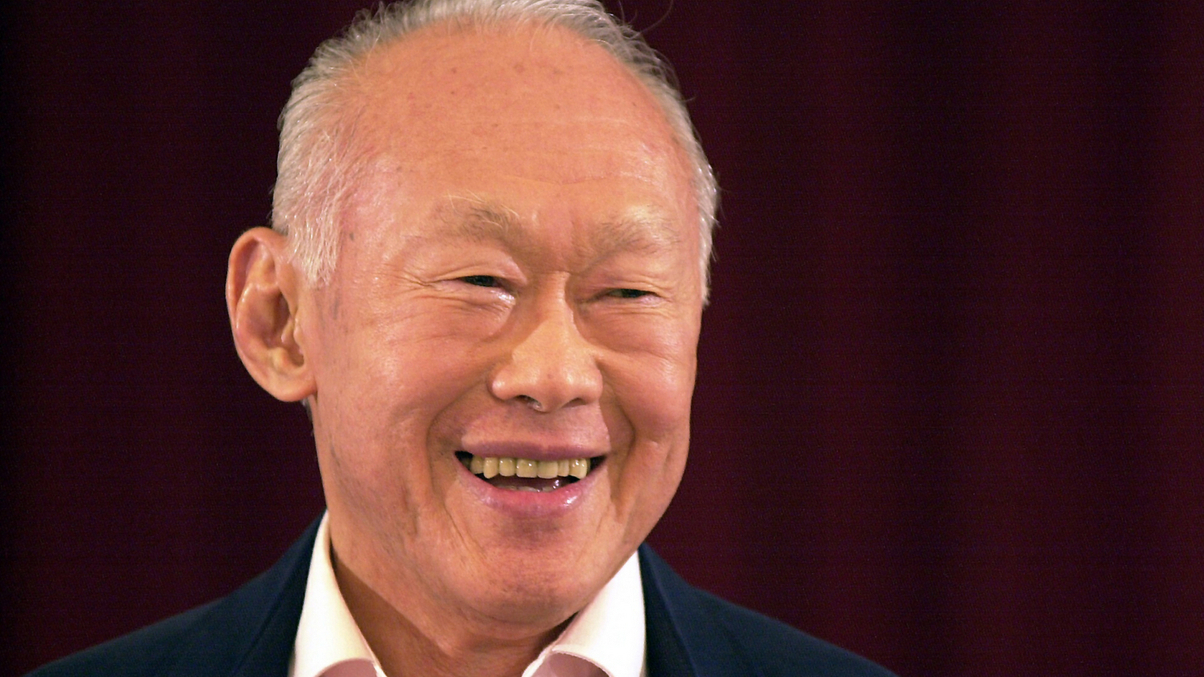

Lee Kuan Yew, 1923-2015

The legacy of Singapore’s visionary leader extends beyond Confucian values or authoritarian capitalism.

Lee Kuan Yew, who passed away in the early hours of Monday, March 23, defined post-war, 20th century Asia more than any leader other than Deng Xiaoping.

Sign in to read on!

Registered users get 2 free articles in 30 days.

Subscribers have full unlimited access to AsianInvestor

Not signed up? New users get 2 free articles per month, plus a 7-day unlimited free trial.

¬ Haymarket Media Limited. All rights reserved.